Jacobus Oma looked sadly at the stockpile of several hundred ancient rosewood logs he had just helped to load onto a Chinese-owned truck in northeastern Namibia. Some were centuries old, so large they dwarfed his small frame.

"The children will never see trees like this in our lives again," he said, recalling how the rosewood’s seed pods were traditionally a vital source of food for indigenous San people like himself during the dry season.

Oma had accompanied the teams that felled the trees earlier this year on the boundary of Khaudum National Park in Namibia’s Okavango region, a part of the San’s ancestral lands.

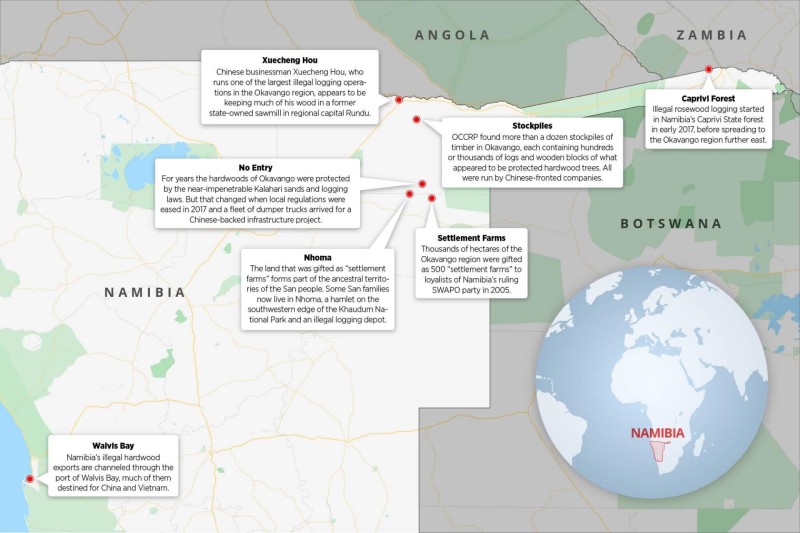

Back in Nhoma, a sparse collection of buildings on the southwestern edge of the park where he lives with his family, Oma told OCCRP he helped load the prized hardwoods for one of the Chinese-fronted companies that dominate the local illegal logging trade here.

“I am not being paid. I am only helping out with the timber loading here,” he said, explaining that he had hoped at least to get something to eat.

Oma’s ripped top and pants were smeared with black stains from moving the wood, some of which had been charred by fires set by local farmers in the hope of rejuvenating the land.

The logs are among thousands of protected trees that have been illegally cut down on land leased as “settlement farms” to political elites and war veterans by Namibia’s ruling South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO) party.

OCCRP found more than a dozen stockpiles of timber along the routes the loggers use, ranging from hundreds to thousands of logs or blocks — squared off trunks with bark still attached. All appeared to be from three protected hardwood species — African rosewood, Zambezi teak, and Kiaat.

A forestry expert described the stockpiles, all run by two Chinese-fronted companies, as evidence of "industrial wood mining."

Despite a moratorium on harvesting these prized hardwoods in Namibia since November 2018, and a ban on trading raw timber since early August, the plunder has continued. On two recent road trips through the Okavango and Zambezi regions, together covering 6,600 kilometers, an OCCRP reporter saw not a single mature African rosewood tree left standing.

The farm leaseholders could have made as much as US$1.5 million per year from selling the wood. But the true winners appear to be the Chinese-fronted companies that control the trade, with timber valued at many millions of dollars exported in just months, according to a government official. Forestry department data and figures from wood brokers on the ground indicate that these exports are declared at just a small fraction of their value, leading to vast sums being lost in uncollected tax revenues.

SWAPO did not respond to a request for comment.

‘They are Finishing the Trees’

A reporter visited the Okavango logging region twice, in October and November. Posing as a prospective wood buyer, he found evidence of illegal logging at every turn, from sawmills operating on the settlement farms to the stockpiles of often-fresh timber along the route.

Though no new three-month harvesting permits have been issued since late 2018, local wood brokers assured the undercover reporter that the paperwork would not be a problem.

“You leave it with me, bra," said one broker in the regional capital of Rundu, a fast-growing frontier city on the Angolan border, who gave his name as Lobo.

Some farmers said they had plentiful Kiaat trees on their land just waiting to be felled. But everywhere, the reporter was told that rosewood trees, which have grown in the region for some 700 years, are now scarce.

"They are finishing the trees now," said one worker who was running a stockpile for a Chinese company in Tam-Tam, in the middle of the logging region. He claimed the 850 blocks stored at the depot, which had been harvested in June, were from the last mature rosewood trees in the area.

The harvesting of hardwoods in Namibia is often massively wasteful. Loggers tend to use only the cores of the trunks of mature trees, ignoring regulations aimed at preventing uncontrolled large-scale harvesting.

OCCRP saw telltale signs that workers on the Okavango settlement farms are using the same methods as in other areas, including big branches left discarded at harvesting sites and the stumps of huge trees.

The timber from the settlement farms was taken to stockpiles, where it was loaded onto trucks mostly bound for Walvis Bay port. Transport permit records at forestry department offices showed it was destined for buyers in China, Vietnam, and South Africa. Most of the addresses listed for the exporting companies in the transport permits appeared to be false, leading to empty fields or residential apartment blocks.

An internal auditors’ report on the logging by Namibia’s Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry (MEFT) estimated that around 32,000 logs or blocks of protected hardwood — equivalent to around 210 truckloads — were moved from Okavango to the port of Walvis Bay between November 2018 and March 2019.

Of that, some 22,000 were stored in warehouses and containers near the port, while “about 10,000 blocks were exported to China and Vietnam," said the report, obtained by OCCRP.

Namibia is a signatory to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which banned international trade in rosewoods in 2017 in part as a response to rising demand for red-wood furniture in Asia.

But the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime noted in its latest World Wildlife Crime report, released this year, that the timber industry is inconsistently regulated.

“Unlike illicit drugs, timber is not sold into illegal markets but rather fed into legal industries where its illegal origin is obscured,” it read. “Timber harvested illegally in one country may be legal to import in another.”

In Namibia, all indigenous hardwood tree species are nominally protected by the Forest Act of 2001, which was designed to prevent uncontrolled logging. But in 2016, Chinese wildcat loggers started shipping illicit timber from Angola, Zambia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo through a Namibian port. And by the following year, the rosewood gold rush had reached Namibia itself, starting in the Caprivi State forest in Zambezi Region before spreading to the settlement farms of Kavango East.

Political Plunder

Around 500 settlement farms in the region, each covering some 2,500 hectares, were handed to war veterans and political elites starting in 2005. The recipients included the current Minister of Home Affairs, Immigration, Safety and Security, Frans Kapofi; a former governor of the Okavango region; the current mayor of Rundu; and several senior civil servants. They did not respond to requests for comment.

Apollonius Kanyinga, who worked at the Ministry of Lands and Resettlement at the time and is now the MEFT’s director for Okavango and Caprivi, secured five farms for himself and his family in a block close to Khaudum National Park.

Kanyinga insisted that he had nothing to do with the fact that his cousin received a farm next to his own two farms. He admitted he was then working for the Lands Ministry, which allocated the farms, but denied he was a deputy director.

The poor soil in the region means most of the land is unsuitable for growing crops. And because the farms lie north of the "Red Line" — a veterinary cordon meant to stop the spread of foot-and-mouth disease across Namibia — they also cannot be used to rear livestock for trade.

That leaves the hardwoods as the only resources of commercial value on the land.

For 26 years, the difficult terrain and local laws protected these trees, the last old-growth rosewoods of the African teak forests left along the banks of the Omuramba-Omatako, an ancient river that is now only a seasonal floodplain.

But in 2017, Forestry Director Joseph Hailwa decided the laws no longer applied to Chinese logging in the Caprivi State Forest and the Okavango Region for own-use permits. With the arrival of Chinese dump trucks that could handle the drive, this meant the farms were open for business.

Old Trees, New Trucks

One key reason Okavango’s forest was left relatively untouched for decades was the difficulty of driving through the near-impenetrable terrain of the Kalahari sands to reach them.

By 2018, the plunder had started. Pictures showing truck after overloaded truck leaving the area caused a national outcry, prompting Environmental Commissioner Teofilus Nghitila to stop issuing new harvesting permits that November.

But the logging has continued. The internal MEFT report found that leaseholders had pressed on, with nearly 400 licenses to fell 600-1,200 trees per farm being handed out by Forestry Director Joseph Hailwa, despite not having the legally required environmental certificate.

Hailwa did not reply to a request for comment.

As the auditors pointed out, because the settlement farms are still technically state land, none of them have the right to sell the trees for profit.

“The trees are currently being treated as if they are the private property of the respective farmers," the report said. "The trees that were harvested by small-scale commercial farmers are state-owned resources and as such should be used to benefit the broader community in the communal areas.”

The report estimated that Namibian farmers could generate an income of around N$24 million ($1.5 million) per year from selling the rosewood trees.

But it seems the Chinese traders are the ones making the real money. Namibia’s Minister of Environment, Forestry and Tourism, Pohamba Shifeta, said timber speculators exported some 75,000 tons of wood valued at N$94 million, (US$6.1 million) or $65 per cubic meter, in the first two months of 2019 alone.

South African hardwood specialist André Swanepoel said the speculators’ earnings are likely far higher, as they tend to under-declare the value of the wood to avoid taxes. He said rosewood would sell for at least $500 per cubic meter on the open market.

Official export data obtained by OCCRP shows Chinese traders declared almost 14,700 tons of rosewood exports between 2017 and 2019 at a total value of around $51,000, less than one percent of the more than $7.35 million the timber would have been worth at $500 a cubic meter.

Shifeta told lawmakers in October that the plunder was possible because of the legal “gray area” around what constitutes processed timber, which can still be exported, and pledged to tighten regulations. But Dr. John Pallett, who is leading a review of the laws for MEFT, said the problem is in the enforcement of these rules — or lack of it.

President Hage Geingob and the ruling SWAPO party have taken full advantage. At a rally in Okavango three weeks before the general election in November 2019, he gave permission for farmers to sell any hardwood they had already harvested, despite a ban on transport permits imposed a year before.

In the presidential election, where Geingob faced a stiff challenge from newcomer Panduleni Itula, he won 83.5 percent of the presidential vote in the Okavango region compared to 35 percent in the capital region, helping him avoid a runoff.

MEFT did not reply to requests for comment for this story. Neither did Geingob's office or SWAPO.

Who’s Hou?

Two Chinese-fronted companies appear to control the trade in illegal hardwood coming out of Okavango.

Little is known about one of them. But the other is New Force Logistics, run by Hou Xuecheng (also known as Jose Hou), a Chinese immigrant with a long criminal record.

Hou has made a career out of skirting the edges of the law since his arrival in Namibia in 2001. A decade later, he moved into the illegal timber trade, harvesting in neighboring Zambia and Angola and moving hundreds of truckloads across their poorly controlled southern borders into Namibia for export to China. When Zambia finally called a halt to the uncontrolled harvesting by early 2017, more than a thousand trucks loaded with timber had been impounded.

Hou’s History

Hou Xuecheng has a history of trading in banned wildlife — and getting away with it.

In November 2017, Namibia’s Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) started investigating allegations of corruption leveled at Forestry Director Hailwa and Hou, confiscating truckloads of his illicitly harvested timber from Caprivi. But Hou successfully challenged the seizures in court and the charges were dropped.

The ACC declined to explain why, despite repeated requests for comment.

Much of the timber was again forfeited to the state after Hou’s foreman, Li Weichao, was convicted of illegal harvesting and fined N$20,000 ($1,300). As of mid-October 2020, thousands of logs were still lying abandoned in Hou’s former lumberyard.

Hou turned his full attention to the settlement farms in Okavango, focusing on the Kavango East region and the last remaining old trees spread out among them.

It was a New Force Logistics truck that a reporter saw Jacobus Oma, the San worker, help load with rosewood logs at the depot in Nhoma. From there, said the truck’s driver, the wood was set to be delivered to a sawmill 550 kilometers away in the regional capital Rundu.

The mill used to be a state-owned enterprise. Now, however, it appears to be taking delivery of Hou’s illegally harvested wood. New Force Logistics trailers were seen parked at the factory, and at one point the reporter observed that the very logs Oma loaded into one of these trailers in Nhoma were at the mill.

On several occasions, OCCRP saw Hou park his silver Volkswagen SUV at the factory and drive inside.

Morvan Foster, a former manager in Hou’s company, said Hou has been working with the sawmill’s new manager, Mike Thukisho, to illegally export rosewood by cutting the logs into planks so they could get around the government decree issued in August that banned trade in unprocessed timber.

“Mike [Thukisho] will claim they are just friends, but they are in business together,” said Foster.

Thukisho denied the allegation, saying he was given permission to use the factory to produce chairs and desks for 1,000 schools, creating jobs for local unemployed youth. At first he said New Force Logistics had been helping to transport timber for the desks, but he then backtracked, saying Hou was planning to process the timber to export to South Africa.

Hou denied to a reporter that he was involved with illegal logging, insisting that Li Weichao worked for someone else. “I only do the transport,” he told OCCRP.

He would not discuss his purported marriage in Namibia, or any of his legal affairs. When pressed on the evidence, he ended the call.

Despite Hou’s apparently thriving business, his employees have not seen much of the cash. A mechanic at his Kawe plant complained that he was promised N$3,000 ($206) a month in wages, but has only been paid half that. Every month since he started work, he said, he has been promised “full pay next month.”